Grade 12: Women's Suffrage in Saskatchewan

"Together on Common Ground

for the Common Good..."

The year 1916 was an extremely important milestone for voting rights in Canada. It was in this year that women were granted the right to vote in the three Prairie Provinces. Saskatchewan was the second province to enfranchise women, with comparatively little controversy or opposition.

The leader of the suffrage movement in Saskatchewan was Violet Clara McNaughton (1879-1968), a British homesteader and social activist. From her position as the organizer and first President of the Women Grain Growers in Saskatchewan, McNaughton encouraged various women's organizations in the province to work together for the cause of women's suffrage. McNaughton brought together women from the Grain Growers, from the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, and from other womens' groups of the time to establish the Provincial Equal Franchise Board to work "together on common ground for the common good..." (The Western Producer, 28 May 1925.)

Even though there were suffrage movements taking place in other provinces across Canada, it was on the Prairies that this movement had the most and earliest success. Ontario and British Columbia followed a year later, and women were granted the voted in national elections in 1918. Some provinces followed much later, and Quebec women were not enfranchised until 1940!

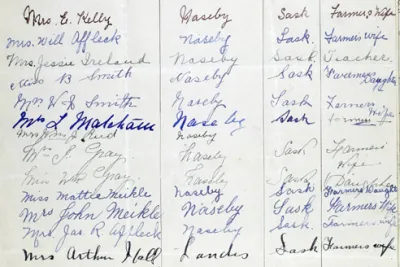

One of thousands of pages of petitions presented to the Government of Saskatchewan before suffrage was granted in 1916 to allow women to vote in provincial elections. Franchise Petitions, 1913, 1916. PAS Photo R-191, Premier's Office, File C.2 to C.11,

Understanding the Prairie Suffrage Movement

Understanding the Prairie Suffrage Movement

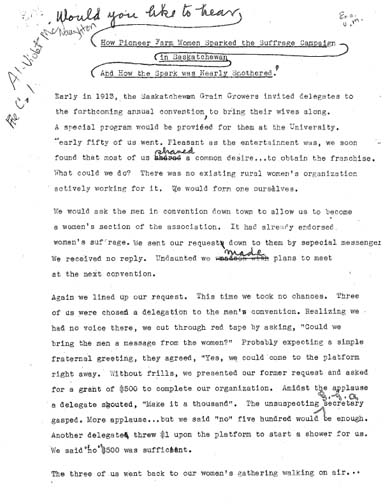

Violet McNaughton Speech: "How We

Got the Franchise in Saskatchewan". n.d.

PAS Photo S-A1-C.1.

Using Primary Source Evidence

The primary source archival documents available below are traces of evidence that can inform our understanding of the suffrage movement in Saskatchewan, and help us understand why prairie suffrage movements found early success.

By studying these sources, we can make inferences about the various authors' purposes, values, and worldviews, in our effort to understand the historical significance of the suffrage movement.

Background Information

Background Information

Violet McNaughton Interview (excerpt) about the women's suffrage movement in Saskatchewan

Audio Recording: CBC Radio Broadcast: Trans-Canada Matinee: Salute to Saskatchewan Women. 1956, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. All rights reserved. PAS Tape R-6334 and PAS Photo S-B2042.

Violet McNaughton Speech: "How We Got the Franchise in Saskatchewan"

Violet McNaughton fonds, Personal Papers, Articles, n.d. File C.1. PAS Photo S-A1.

Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan Entry for "Woman Suffrage"

Erma Stocking, Zoa Haight, Mrs. McNeal, Violet McNaughton, and

Mrs. Flatt of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association, Women's Section,

in Moose Jaw, 1914. PAS Photo R-B4482

Photograph of Violet McNaughton

ca. 1920. PAS Photo S-B2042

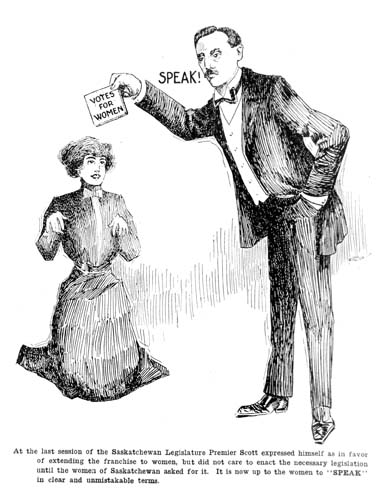

Editorial Cartoons

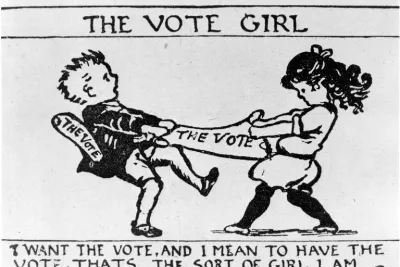

"Votes for Women": editorial cartoon

showing Premier Walter Scott

making women beg for the vote

Grain Growers' Guide, 26 February 1913

PAS Photo S-B6493

Articles

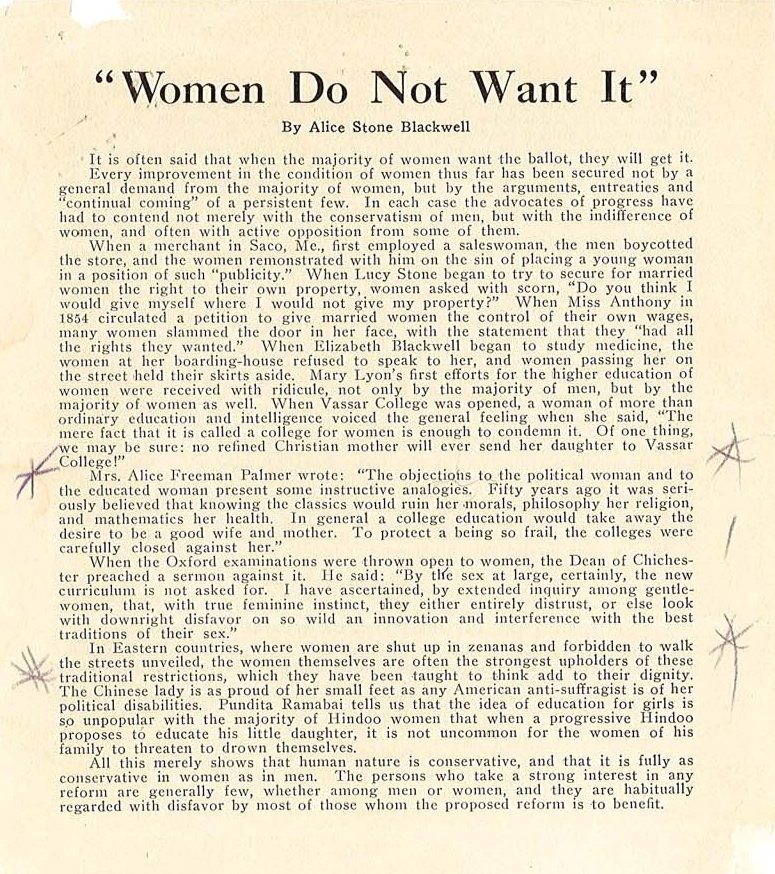

"Women Do Not Want It," by Alice S.

Blackwell, n.d. Violet McNaughton fonds.

Equal Franchise League, 1914-1918

PAS Photo S-A1-E.18,

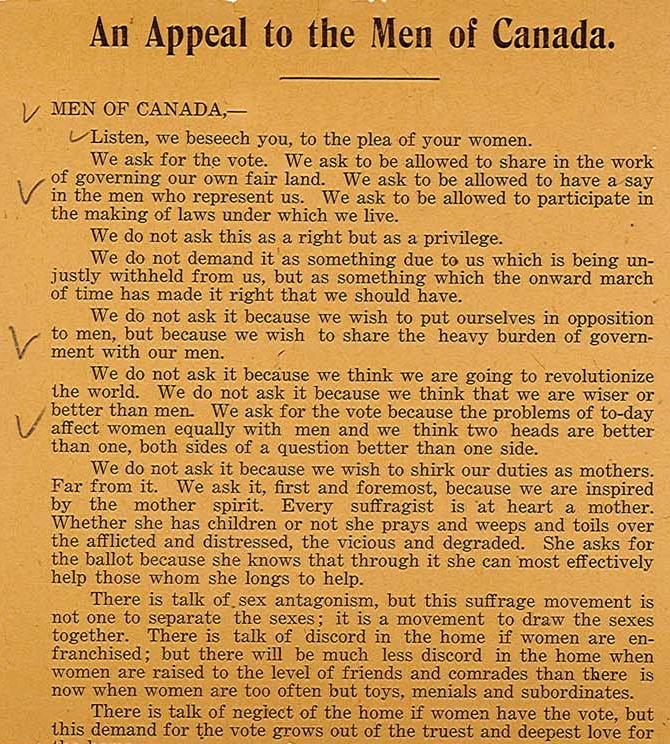

"An Appeal to the Men of Canada,"

Montreal Suffrage Association, n.d.

Violet McNaughton fonds,

Equal Franchise League, 1914-1918.

PAS Photo S-A1-E.18,

"Some Women Will Vote Wisely,

Some Foolishly, and Some Not At All,"

The Saturday Press & Prairie Farm,

1 May 1915, 6. Equal Franchise League, 1914-1918.

Violet McNaughton fonds,

PAS Photo S-A1-E.18,

Other Article Titles:

- "Women Receive the Vote from Scott Government at Memorable St. Valentine's Day Assembly," Regina Morning Leader, 15 February 1916.

- "Votes for Women Are Asked in Petition," Regina Morning Leader, 30 April 1915, 8.

- "Petition for Women's Votes Presented," Regina Morning Leader, 28 May 1915, 12.

- "Equal Suffrage in Saskatchewan," The Saturday Press & Prairie Farmer, 16 February 1916, 1.

- News story about the positive reception received by suffrage lobbyists who presented petitions to the Premier in the Saskatchewan Legislature,

which resulted in changes to Saskatchewan's franchise legislation and allowing women to vote in provincial elections.

The Saturday Press and Prairie Farm, 19 February 1916, 1. - Women's Section, including "Suffrage Board Will Meet in October" and "Eloquent Speeches by Suffragists,"

The Evening Province & Standard (Regina), 28 May 1916, 5. - "Letters from Readers: Votes for Women," The Montreal Weekly Witness, 2 October 1917, 13.

- "Women and Political Parties," by Mrs. H.H. McKinney Saskatoon Star, 13 December 1918

Letters

![Letter from Lillian B. Thomas, Winnipeg, to Violet McNaughton, 17 September [ca. 1916-1919?]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/a1_e18_21_22-1.jpg)

Letter from Lillian B. Thomas, Winnipeg,

toViolet McNaughton, 17 September

[1916-1919?]. Violet McNaughton fonds,

PAS Photo S-A1-E.18,

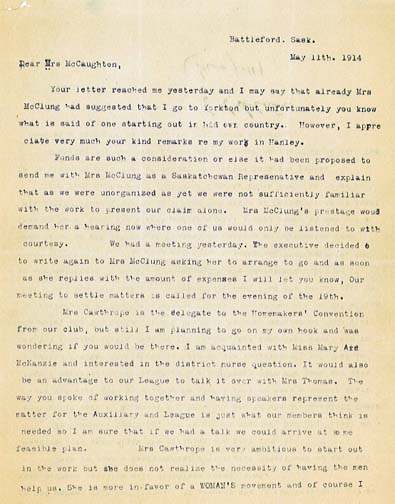

Letter from Effie Laurie Storer,

Battleford, to Violet McNaughton,

11 May 1914. Violet McNaughton fonds.

PAS Photo S-A1-E.18,

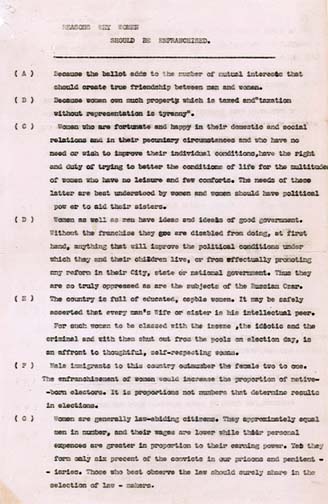

"Reasons Why Women Should

Be Enfranchised," ca. 1914-1916.

Violet McNaughton fonds,

PAS Photo S-A1-E.18.

Other Letters:

- "Reasons Why Women Should Be Enfranchised," ca. 1914-1916.

- Letter from Premier Walter Scott, Regina, to Violet McNaughton, 16 February 1916.

- Letter from M.A. Lawton, Yorkton, and Nellie McClung, Edmonton, to Violet McNaughton, 28 June 1916.

- Letter from Lillian B. Thomas, Winnipeg, to Violet McNaughton, 21 December 1916.

Curriculum

Historical Thinking Concepts:

Evidence: How do we know what we know about the past?

Guidepost 1: History is an interpretation based on inferences made from primary sources.

Guidepost 2: Asking good questions about a source can turn it into evidence.

Guidepost 3: Sourcing often begins before a source is read, with questions about who created it and when it was created. It involves inferring from the source the author's or creator's purposes, values, and worldview.

Guidepost 4: A source should be analyzed in relation to the context of its historical setting; the conditions and worldviews prevalent at the time.

Guidepost 5: Inferences made from a source can never stand alone. They should always be corroborated -- checked against other sources (primary or secondary).

Historical Significance: How do we decide what is important to learn about the past?

Guidepost 2: Events, people, or developments have historical significance if they are revealing. That is, they shed light on enduring or emerging issues in history or contemporary life.

Guidepost 3: Historical significance is constructed. That is, events, people, and developments meet the criteria for historical significance when they are shown to occupy a meaningful place in a narrative.

Continuity and Change: How can we make sense of the complex flows of history.

Guidepost 4: Periodization helps us organize our thinking about continuity and change. It is a process of interpretation, by which we decide which events or developments constitute a period of history.

Cause and Consequence: Why do events happen, and what are their impacts?

Guidepost 1: Change is driven by multiple causes, and results in multiple consequences. These create a web of interrelated short-term and long-term causes and consequences.

Guidepost 3: Events result from the interplay of two types of factors: (1) historical actors, who are people (individuals or groups) who take actions that cause historical events, and (2) the social, political, economic, and cultural conditions within which the actors operate.

From The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts by Peter Seixas and Tom Morton (Toronto: Nelson Education, 2013)