Grade 8: The Reserve Pass System and Its Impact on Treaty Relationships

This learning package allows students to study samples of original reserve passes and correspondence about the reserve pass system while considering the impact of that system on First Nations communities and individuals, on Canadian treaty relationships, and on basic human rights.

The lesson asks this essential question: How has power been used and abused in order to control movements and rights of minority populations in Canada and around the world?

What was the Reserve Pass System?

In 1885, a pass system was instituted by Indian Affairs officials -- with the knowledge and consent of Prime Minister John A. Macdonald -- to control the off-reserve movements of First Nations people in western Canada.

First Nations people were required to remain on their reserves unless they obtained a pass that specified the purpose of their travel and the duration of their absence, which had to be signed by the Indian agent or farm instructor.

Although never enacted in law, and frequently circumvented by First Nations communities, the pass system continued to be operated by Indian Affairs employees until at least the mid-1930s.

Background Article

Read the background article by F. Laurie Barron, “The Indian Pass System in the Canadian West, 1882-1935,” Prairie Forum 13, no. 1 (1988): 25-42. Gratefully provided with permission from University of Regina Press.

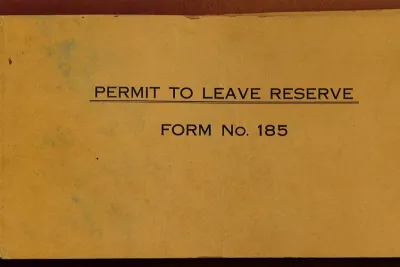

Cover of a reserve pass book used at the Duck Lake Agency. Dept. of Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Permits to Leave Reserve, 1889-1901, 1904-1905, 1932-1934. PAS, S-E19. File 35.c.

Sample Reserve Passes

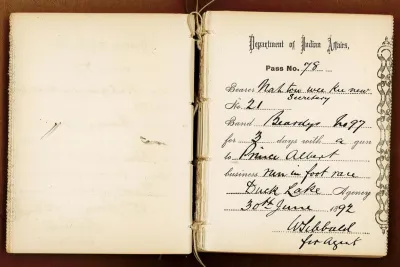

Duck Lake Agency reserve pass issued to Nah tow wee kee new (Secretary), who was traveling to Prince Albert to run in a foot race, 1892. Dept. of Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Permits to Leave Reserve, 1889-1901, 1904-1905, 1932-1934. PAS, S-E19 File 35.a.

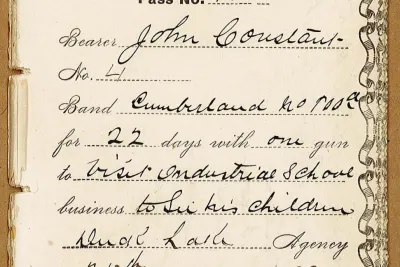

Duck Lake Agency reserve pass issued to John Constant, who was traveling to visit his children at industrial school, 1889. Dept. of Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Permits to Leave Reserve, 1889-1901, 1904-1905, 1932-1934. PAS S-E19 File 35.a.

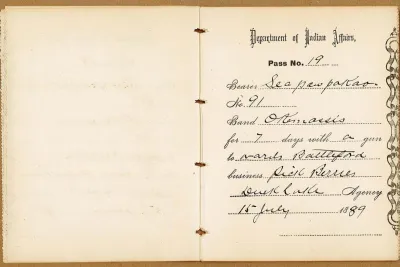

Duck Lake Agency reserve pass issued to Seepawpakao, who was traveling to pick berries, 1889. Dept. of Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Permits to Leave Reserve, 1889-1901, 1904-1905, 1932-1934. PAS, S-E19. File 35.a.

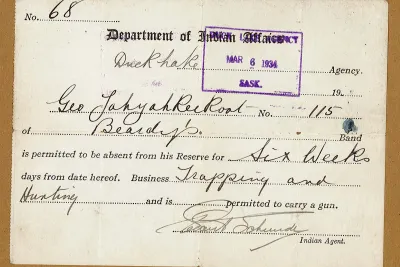

Duck Lake Agency reserve pass issued to George Yahyahkeekoot, who was traveling for hunting and trapping, 1934. Dept. of Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Requests to Leave Reserve, 1931-1934. PAS, S-E19. File 36.

Duck Lake Agency reserve pass issued to Espanas, who was traveling to Battleford and Fort PItt to visit his aunts, 1890. Dept. of Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Permits to Leave Reserve, 1889-1901, 1904-1905, 1932-1934. PAS, S-E19. File 35.a.

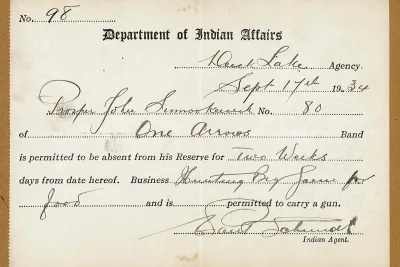

Duck Lake Agency reserve pass issued to Proper John Simookeesick, who was traveling for hunting big game, 1934. Dept. of Indian & Northern Affairs Canada. Requests to Leave Reserve, 1931-1934. PAS, S-E19. File 36.

Curriculum

DR8.2 - Describe the influence of the treaty relationship on Canadian identity.

DR8.3 - Assess how historical events in Canada have affected the present

Canadian identity.

Citizen Education Inquiry:

Engaged Citizens 8 - What is Canada's Identity?

What is the impact of history on Canada's identity (EC8, pp. 15-18)

What is the influence of Treaty Relationships on Canadian identify?

(EC8, pp. 12-14)

Treaty Education Outcomes:

TPP8: Treaty Promises & Provisions: Assess whether the terms of treaty

have been honoured and to what extent the treaty obligations

have been fulfilled.

Historical Thinking Concepts:

Cause and Consequence: Why do events happen, and what are their impacts?

Guidepost 1: Change is driven by multiple causes, and results in multiple consequences. These create a complex web of interrelated short-term and long-term causes and consequences.

Historical Perspective: How can we better understand the people of the past?

Guidepost 1: An ocean of difference can ie between current worldviews (beliefs, values and motivations) and those of earlier periods of history.

Guidepost 5: Different historical actors have diverse perspectives on the events in which they are involved. Exploring these is key to understanding historical events.

Ethical Dimension: How can history help us live in the present?

Guidepost 2: Reasoned ethical judgments of past actions are made by taking into account the historical context of the actors in question.

Guidepost 4: A fair assessment of the ethical implications of history can inform us of our responsibilities to remember and respond to contributions, sacrifices, and injustices of the past.

Continuity and Change: How can we make sense of the complex flows of history?

Guidepost 3: Process and decline are broad evaluations of change over time. Depending on the impacts of change, progress for one people may be decline for another.

Guidepost 4: Periodization helps us organize our thinking about continuity and change. It is a process of interpretation, by which we decide which events or developments constitute a period of history.

From The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts by Peter Seixas and Tom Morton (Toronto: Nelson Education, 2013)